Low E String Is Reading F on Tuner When Checking Intonation

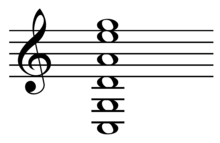

The range of a guitar with standard tuning

Guitar tunings are the assignment of pitches to the open strings of guitars, including acoustic guitars, electric guitars, and classical guitars. Tunings are described by the detail pitches that are fabricated by notes in Western music. Past convention, the notes are ordered and bundled from the lowest-pitched string (i.due east., the deepest bass-sounding note) to the highest-pitched cord (i.e., the highest sounding note), or the thickest string to thinnest, or the lowest frequency to the highest.[1] This sometimes confuses beginner guitarists, since the highest-pitched string is referred to equally the 1st string, and the lowest-pitched is the 6th string.[ citation needed ]

Standard tuning defines the string pitches as Due east, A, D, G, B, and Eastward, from the everyman pitch (low Eii) to the highest pitch (high East4). Standard tuning is used by most guitarists, and frequently used tunings can be understood as variations on standard tuning. To aid in memorising these notes, mnemonics are used, for case, Eddy Ate Dynamite, Good Bye Eddy.[2]

The term guitar tunings may refer to pitch sets other than standard tuning, also called nonstandard, alternative, or alternating.[3] There are hundreds of these tunings, often with small variants of established tunings. Communities of guitarists who share a common musical tradition frequently use the same or like tuning styles.

Standard and alternatives [edit]

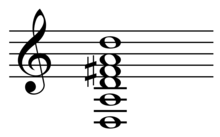

In standard tuning, the C-major chord has multiple shapes considering of the irregular major-third betwixt the M- and B-strings. Three such shapes are shown above.

Standard [edit]

Standard tuning is the tuning most ofttimes used on a 6-string guitar and musicians assume this tuning by default if a specific alternate (or scordatura) is not mentioned. In scientific pitch note,[4] the guitar'south standard tuning consists of the following notes: E two–A 2–D 3–One thousand 3–B 3–Eastward 4 .

-

String frequencies

of standard tuningCord Frequency Scientific

pitch

notation1 (Eastward) 329.63 Hz Eastward 4 2 (B) 246.94 Hz B 3 3 (One thousand) 196.00 Hz G iii 4 (D) 146.83 Hz D 3 5 (A) 110.00 Hz A2 6 (E) 082.41 Hz Eastward ii

The guitar is a transposing instrument; that is, music for guitars is notated i octave higher than the truthful pitch. This is to reduce the need for ledger lines in music written for the instrument, and thus simplify the reading of notes when playing the guitar.[5]

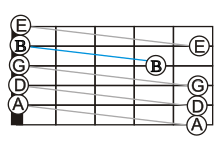

Standard tuning provides reasonably elementary fingering (fret-manus motion) for playing standard scales and basic chords in all major and minor keys. Separation of the get-go (high E) and 2d (B) string, as well every bit the separation between the 3rd (G), fourth (D), fifth (A), and sixth (depression Eastward) strings by a 5-semitone interval (a perfect quaternary) allows the guitarist to play a chromatic scale with each of the four fingers of the fretting hand controlling one of the outset iv frets (index finger on fret i, little finger on fret iv, etc.) only when the hand is in the first position.[6]

The open up notes of the 2nd (B) and third (G) strings are separated by four semitones (a major third). This tuning pattern of (low) fourths, one major third,[a] and 1 fourth was inherited past the guitar from its predecessor musical instrument, the viol. The irregular major 3rd breaks the fingering patterns of scales and chords, then that guitarists accept to memorize multiple chord-shapes for each chord. Scales and chords are simplified past major thirds tuning and all-fourths tuning, which are regular tunings maintaining the aforementioned musical interval between consecutive open-string notes.[7]

-

Chromatic note progression 0 I Two III Iv String open 1st fret

(alphabetize)2nd fret

(heart)tertiary fret

(ring)4th fret

(piffling)6th E ii F 2 F ♯

ii / G ♭

iiThou 2 G ♯

2 / A ♭

two5th A 2 A ♯

2 / B ♭

2B 2 C 3 C ♯

3 / D ♭

34th D iii D ♯

three / Eastward ♭

3E 3 F 3 F ♯

iii / G ♭

3third Chiliad three G ♯

iii / A ♭

3A 3 A ♯

3 / B ♭

3B iii 2nd B 3 C 4 C ♯

iv / D ♭

ivD 4 D ♯

4 / E ♭

41st East 4 F 4 F ♯

4 / G ♭

fourG 4 G ♯

4 / A ♭

4

Alternative [edit]

Alternative ("alternating") tuning refers to any open up-cord notation arrangement other than standard tuning. These offering different kinds of deep or ringing sounds, chord voicings, and fingerings on the guitar. Culling tunings are common in folk music where the guitar may exist called upon to produce a sustained note or chord known equally a drone. This often gives folk music its haunting and lamenting ambient due to the atmosphere and mood that the notes make.[8] Alternative tunings change the fingering of common chords when playing the guitar, and this can ease the playing of certain chords while simultaneously increase the difficulty of playing other chords.

Some tunings are used for detail songs, and may be named after the song'southward title. There are hundreds of these tunings, although many are slight variations of other alternate tunings.[nine] Several alternative tunings are used regularly past communities of guitarists who share a common musical tradition, such as American folk or Celtic folk music.[x]

The various culling tunings have been grouped into the following categories:[eleven]

- dropped[12] [13]

- open[14]

- both major and pocket-sized (cross note)[fifteen] [13] [16]

- modal[13] [17]

- instrumental (based on other stringed instruments)

- miscellaneous ("special").[13] [16] [18]

Joni Mitchell is known for developing a autograph descriptive method of noting guitar tuning where the first letter documents the note of the everyman string, and is followed by the relative fret (half-step) offsets required to obtain the pitch of the next (higher) string.[19] This scheme highlights pitch relationships and simplifies the process of comparing dissimilar tuning schemes.

String gauges [edit]

String judge refers to the thickness and diameter of a guitar string, which influences the overall sound and pitch of the guitar depending on the guitar string used.[20] Some culling tunings are hard or even incommunicable to achieve with conventional guitars due to the sets of guitar strings, which accept gauges optimized for standard tuning. With conventional sets of guitar strings, some higher tunings increase the string-tension until playing the guitar requires significantly more than finger-strength and stamina, or even until a string snaps or the guitar is warped. However, with lower tunings, the sets of guitar strings may be loose and buzz. The tone of the guitar strings is besides negatively afflicted by using unsuitable string gauges on the guitar.

By and large, culling tunings benefit from re-stringing of the guitar with string gauges purposefully chosen to optimize particular tunings[21] past using lighter strings for higher-pitched notes (to lower the tension of the strings) and heavier strings for lower-pitched notes (to prevent string buzz and vibration).

Dropped tunings [edit]

A dropped tuning is one of the categories of alternative tunings and the process starts with standard tuning and typically lowers the pitch of ("drops") merely a single cord, almost ever the lowest-pitched (E) cord on the guitar.

The drop D tuning is mutual in electric guitar and heavy metal music.[22] [23] The low E string is tuned downward one whole footstep (to D) and the balance of the strings remain in standard tuning. This creates an "open power chord" (three-annotation fifth) with the low iii strings (DAD).

There also exists double-drop D tuning, in which both E strings are downward-tuned a whole step (to D). The rest of the strings keep their original pitch.

Although the drop D tuning was introduced and developed by blues and classical guitarists, it is well known from its usage in contemporary heavy metal and hard rock bands. Early difficult stone songs tuned in drop D include The Beatles' "I Want You (She'south So Heavy)" and Led Zeppelin's "Moby Dick", both first released in 1969.[24] Tuning the everyman string one tone downward, from E to D, allowed these musicians to acquire a heavier and darker sound than in standard tuning. Without needing to tune all strings (Standard D tuning), they could tune but one, in gild to lower the cardinal. Driblet D is also a convenient tuning, because it expands the calibration of an musical instrument by two semitones: D and D ♯ .

In the mid 1980s, three alternative rock bands, King'south X, Soundgarden and Melvins, influenced by Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath, made extensive use of drop D tuning.[25] While playing power chords (a chord that includes the prime, 5th and octave) in standard tuning requires a player to utilize ii or three fingers, drop D tuning needs just one, like in technique to playing barre chords.[26] It immune them to utilize different methods of articulating power chords (legato for example) and more than importantly, information technology allowed guitarists to modify chords faster. This new technique of playing power chords introduced by these early grunge bands was a great influence on many artists, such as Rage Against the Car and Tool. The aforementioned driblet D tuning and then became common practice among alternative metal acts such every bit the band Helmet, who used the tuning a great bargain throughout their career and would later influence many culling metal and nu metal bands.[27] [28]

Open tunings [edit]

Ry Cooder plays slide guitar with open tunings

An open tuning allows the guitarist to play a chord by strumming the open strings (no strings fretted).

Open tunings may be chordal or modal. In chordal open tunings, the open chord consists of at to the lowest degree three different pitch classes. In a given key, these are the root note, its 3rd and its 5th, and may include all the strings or a subset. The tuning is named for the base chord when played open up, typically a major chord, and all like chords in the chromatic calibration are played by disallowment all strings across a single fret.[29] Open up tunings are common in blues and folk music.[30] These tunings are frequently used in the playing of slide and lap-slide ("Hawaiian") guitars, and Hawaiian slack cardinal music.[29] [31] A musician who is well-known for using open up tuning in his music is Ry Cooder, who uses open tunings when playing the slide guitar.[30]

Most modernistic music uses equal temperament because it facilitates the ability to play the guitar in any key—as compared to just intonation, which favors sure keys, and makes the other keys audio less in melody.[32]

Repetitive open-tunings are used for two classical not-Spanish guitars. For the English guitar, the open up chord is C major (C–E–G–C–E–Yard);[33] for the Russian guitar, which has vii strings, it is G major (D–Grand–B–D–1000–B–D).[34] [35]

When the open strings constitute a minor chord, the open up tuning may sometimes be chosen a cross-annotation tuning.

Major cardinal tunings [edit]

Major open-tunings give a major chord with the open strings.

-

Open tunings Major triad Repetitive Overtones Other (ofttimes nigh popular)

Open up A (A,C ♯ ,E) A–C ♯ –E–A–C ♯ –E A–A–Eastward–A–C ♯ –E E–A–C ♯ –East–A–E Open B (B,D ♯ ,F ♯ ) B–D ♯ –F ♯ –B–D ♯ –F ♯ B–B–F ♯ –B–D ♯ –F ♯ B–F ♯ –B–F ♯ –B–D ♯ Open C (C,Eastward,G) C–E–G–C–East–G C–C–G–C–E–K C–G–C–G–C–E Open up D (D,F ♯ ,A) D–F ♯ –A–D–F ♯ –A D–D–A–D–F ♯ –A D–A–D–F ♯ –A–D Open up Due east (E,1000 ♯ ,B) Eastward–G ♯ –B–E–G ♯ –B E–Due east–B–Due east–G ♯ –B Eastward–B–E–One thousand ♯ –B–E Open F (F,A,C) F–A–C–F–A–C F–F–C–F–A–C C–F–C–F–A–F Open up G (G,B,D) Thou–B–D–Thousand–B–D Chiliad–Grand–D–1000–B–D D–G–D–G–B-D

Open up tunings ofttimes tune the everyman open notation to C, D, or E and they often tune the highest open up note to D or Eastward; tuning downwardly the open up string from E to D or C avoids the risk of breaking strings, which is associated with tuning upwardly strings.

Open D [edit]

The open D tuning (D–A–D–F ♯ –A–D), also called "Vestopol" tuning,[36] is a common open tuning used by European and American/Western guitarists working with alternative tunings. The Allman Brothers instrumental "Little Martha" used an open-D tuning raised one half step, giving an open E♭ tuning with the same intervallic relationships as open D.[37]

Open C [edit]

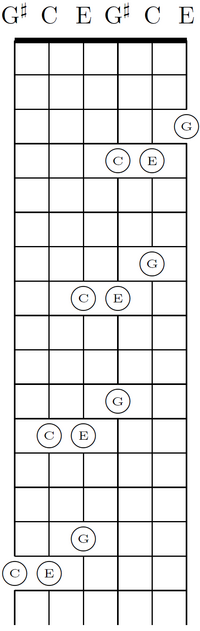

The English guitar used a repetitive open-C tuning (with distinct open notes C–Eastward–G–C–E–G) that approximated a major-thirds tuning.[33] This tuning is evident in William Ackerman'southward vocal "Townsend Shuffle", besides every bit past John Fahey for his tribute to Mississippi John Injure.[38] [39]

The C–C–Chiliad–C–East–M tuning uses some of the harmonic sequence (overtones) of the notation C.[40] [41] This overtone-series tuning was modified by Mick Ralphs, who used a high C note rather than the high G note for "Can't Go Enough" on Bad Company. Ralphs said, "It needs the open up C to have that ring," and "information technology never really sounds correct in standard tuning".[42]

Open up 1000 [edit]

Mick Ralphs' open-C tuning was originally an open up-G tuning, which listed the initial six overtones of the One thousand note, namely Yard–One thousand–D–G–B–D; Ralphs used this open up-G tuning for "Hey Hey" and while writing the demo of "Can't Get Enough".[42]

Open-M tuning usually refers to D–G–D–Thou–B–D. The open K tuning variant G–Thousand–D–Grand–B–D was used by Joni Mitchell for "Electricity", "For the Roses" and "Hunter (The Proficient Samaritan)".[43] Truncating this tuning to G–D–G–B–D for his five-string guitar, Keith Richards uses this overtones-tuning on The Rolling Stones's "Honky Tonk Women", "Brownish Sugar" and "Start Me Up".[44]

The seven-string Russian guitar uses the open-G tuning D–G–B–D–One thousand–B–D, which contains mostly major and pocket-sized thirds.[45] [35]

Creating whatever kind of open up tuning [edit]

Any kind of chordal tuning tin be achieved, just by using the notes in the chord and tuning the strings to those notes. For case, Asus4 has the notes A, D, E. By tuning the strings to merely those notes, information technology creates a chordal Asus4 tuning.

-

Power chord (fifths) open tunings:[46] A5 East–A–Eastward–A–A–East B5 F ♯ –B–F ♯ –B–B–F ♯ C5 C–G–C–M–G–G D5 D–A–D–A–D–D Due eastfive East–B–E–E–B–E F5 F–C–C–C–C–F G5 D–Thou–D–G–D–G

Bass players may omit the last two strings.

Minor or "cantankerous-annotation" tunings [edit]

Cross-note tunings include a minor third, and so giving a pocket-size chord with open strings. Fretting the minor-third string at the first fret produces a major-tertiary, and so allowing a i-finger fretting of a major chord.[47] By contrast, it is more difficult to fret a minor chord using an open up major-chord tuning.

Bukka White and Skip James[48] are well-known for using cross-notation E-minor in their music.

Other open chordal tunings [edit]

Some guitarists choose open tunings that use more complex chords, which gives them more than bachelor intervals on the open strings. Csix, East6, E7, Esix/9 and other such tunings are mutual among lap-steel players such as Hawaiian slack-primal guitarists and country guitarists, and are likewise sometimes practical to the regular guitar by bottleneck (a slide repurposed from a glass canteen) players striving to emulate these styles. A common Csix tuning, for instance, is C–E–G–A–C–E, which provides open up major and pocket-size thirds, open major and minor sixths, fifths, and octaves. Past contrast, virtually open up major or open pocket-sized tunings provide only octaves, fifths, and either a major third/sixth or a modest third/sixth—but not both. Don Helms of Hank Williams band favored C6 tuning; slack-key artist Henry Kaleialoha Allen uses a modified C6/seven (C6 tuning with a B ♭ on the bottom); Harmon Davis favored East7 tuning; David Gilmour has used an open up G6 tuning.

Modal tunings [edit]

Modal tunings are open tunings in which the open strings of the guitar practice not produce a tertian (i.e., major or pocket-sized, or variants thereof) chord. The strings may be tuned to exclusively present a unmarried interval (all fourths; all fifths; etc.) or they may exist tuned to a not-tertian chord (unresolved suspensions such as E–A–B–Eastward–A–E, for example). Modal open tunings may use only i or two pitch classes across all strings (as, for example, some metallic guitarists who tune each string to either E or B, forming "power chords" of ambiguous major/minor tonality).

Popular modal tunings include D Modal (D-M-D-G-B-Due east) and C Modal (C-G-D-M-B-D).

Lowered (standard) [edit]

Derived from standard EADGBE, all the strings are tuned lower by the same interval, thus providing the same chord positions transposed to a lower key. Lower tunings are pop among rock and heavy metal bands. The reason for tuning downwards below the standard pitch is usually either to accommodate a vocalist'due south song range or to go a deeper/heavier sound or pitch.[49] Mutual examples include:

Eastward♭ tuning [edit]

Rock guitarists (such as Jimi Hendrix on the songs Voodoo Child (Slight Return) and Fiddling Wing) occasionally melody all their strings down by one semitone to obtain Eastward♭ tuning. This makes the strings easier to bend when playing and with standard fingering results in a lower key.[l]

D tuning [edit]

D Tuning, besides called One Step Lower, Whole Step Downwardly, Full Pace or D Standard, is another alternative. Each string is lowered by a whole tone (two semitones) resulting in D-G-C-F-A-D. It is used mostly by heavy metallic bands to achieve a heavier, deeper sound, and by blues guitarists, who employ it to arrange cord bending and by 12-string guitar players to reduce the mechanical load on their instrument. Amongst musicians, Elliott Smith was known to use D tuning as his main tuning for his music. It was too used for several songs on The Velvet Secret'southward anthology The Velvet Hole-and-corner & Nico.

Regular tunings [edit]

| Regular tunings | |

|---|---|

For regular guitar-tunings, the distance between consecutive open-strings is a abiding musical-interval, measured by semitones on the chromatic circumvolve. The chromatic circle lists the twelve notes of the octave. | |

| Basic information | |

| Aliases | Uniform tunings |

| Advanced data | |

| Advantages | Simplifies learning by beginners and improvisation by advanced guitarists |

| Disadvantages | Replicating the open chords ("cowboy chords") of standard tuning is difficult; intermediate guitarists must relearn the fretboard and chords. |

| Regular tunings (semitones) | |

| Trivial (0) | |

| Small-scale thirds (3) | |

| Major thirds (iv) | |

| All fourths (5) | |

| Augmented fourths (6) | |

| New standard (7, three) | |

| All fifths (7) | |

| Modest sixths (8) | |

| Guitar tunings | |

In the standard guitar-tuning, one major-third interval is interjected amid four perfect-4th intervals. In each regular tuning, all string successions have the same interval.

Chords can exist shifted diagonally in major-thirds tuning and other regular tunings. In standard tuning, chords alter their shape because of the irregular major-third G-B.

In standard tuning, there is an interval of a major third between the second and third strings, and all the other intervals are fourths. The irregularity has a price. Chords cannot be shifted effectually the fretboard in the standard tuning E–A–D–G–B–Eastward, which requires iv chord-shapes for the major chords. There are separate chord-forms for chords having their root note on the third, fourth, fifth, and sixth strings.[51] These are called inversions.

In contrast, regular tunings have equal intervals betwixt the strings,[52] and and then they have symmetrical scales all along the fretboard. This makes it simpler to translate chords. For the regular tunings, chords may exist moved diagonally around the fretboard. The diagonal movement of chords is especially uncomplicated for the regular tunings that are repetitive, in which case chords tin be moved vertically: Chords can be moved three strings up (or downwards) in major-thirds tuning, and chords can be moved two strings upward (or down) in augmented-fourths tuning. Regular tunings thus appeal to new guitarists and besides to jazz-guitarists, whose improvisation is simplified past regular intervals.

On the other hand, five- and six-string open chords ("cowboy chords") are more than difficult to play in a regular tuning than in standard tuning. Instructional literature uses standard tuning.[53] Traditionally a course begins with the hand in first position,[54] that is, with the left-paw covering frets ane–four.[55] Offset players first acquire open chords belonging to the major keys C, One thousand, and D. Guitarists who play mainly open chords in these three major-keys and their relative small-keys (Am, Em, Bm) may adopt standard tuning over many regular tunings,[56] [57] On the other hand, minor-thirds tuning features many barre chords with repeated notes,[58] properties that appeal to acoustic-guitarists and beginners.

Major thirds and perfect fourths [edit]

Standard tuning mixes a major third (M3) with its perfect fourths. Regular tunings that are based on either major thirds or perfect fourths are used, for example, in jazz.

All fourths tuning E2–A2–D3–Giii–Cfour–Fiv keeps the lowest four strings of standard tuning, changing the major third to a perfect 4th.[59] [60] Jazz musician Stanley Jordan stated that all-fourths tuning "simplifies the fingerboard, making it logical".[61]

Major-thirds tuning (M3 tuning) is a regular tuning in which the musical intervals between successive strings are each major thirds, for instance E2–G ♯ 2–C3–E3–G ♯ 3–C4.[62] [63] [64] [65] Unlike all-fourths and all-fifths tuning, M3 tuning repeats its octave after three strings, which simplifies the learning of chords and improvisation.[53] This repetition provides the guitarist with many possibilities for fingering chords.[62] [65] With six strings, major-thirds tuning has a smaller range than standard tuning; with seven strings, the major-thirds tuning covers the range of standard tuning on six strings.[63] [64] [65]

Major-thirds tunings require less hand-stretching than other tunings, because each M3 tuning packs the octave'southward twelve notes into four consecutive frets.[63] [66] The major-third intervals let the guitarist play major chords and pocket-size chords with two iii consecutive fingers on two consecutive frets.[67]

Chord inversion is especially simple in major-thirds tuning. The guitarist tin capsize chords past raising one or ii notes on three strings—playing the raised notes with the aforementioned finger every bit the original notes. In dissimilarity, inverting triads in standard and all-fourths tuning requires iii fingers on a span of four frets.[68] In standard tuning, the shape of an inversion depends on the interest of the major-tertiary between the second and third strings.[69]

All fifths and "new standard tuning" [edit]

New Standard Tuning'south open strings

- C2–K2–D3–A3–Eastward4–Bfour

All-fifths tuning is a tuning in intervals of perfect fifths like that of a mandolin or a violin; other names include "perfect fifths" and "fifths".[lxx] It has a wide range. Its implementation has been impossible with nylon strings and has been difficult with conventional steel strings. The high B makes the first string very taut, and consequently, a conventionally gauged string easily breaks.

Jazz guitarist Carl Kress used a variation of all-fifths tuning—with the lesser four strings in fifths, and the peak 2 strings in thirds, resulting in B ♭ 1–F2–C3–M3–B3–Div. This facilitated tenor banjo chord shapes on the lesser four strings and plectrum banjo chord shapes on the meridian 4 strings. Contemporary New York jazz-guitarist Marty Grosz uses this tuning.

All-fifths tuning has been approximated past the so-called "New Standard Tuning" (NST) of King Carmine's Robert Fripp, which NST replaces all-fifths' high B4 with a high G4. To build chords, Fripp uses "perfect intervals in fourths, fifths and octaves", so avoiding minor thirds and especially major thirds,[71] which are slightly sharp in equal temperament tuning (in comparison to thirds in merely intonation). Information technology is a challenge to adapt conventional guitar-chords to new standard tuning, which is based on all-fifths tuning.[b] Some closely voiced jazz chords get impractical in NST and all-fifths tuning.[73]

Instrumental tunings [edit]

These are tunings in which some or all strings are retuned to emulate the standard tuning of some other musical instrument, such as a lute, banjo, cittern, mandolin, etc. Many of these tunings overlap other categories, especially open and modal tunings.

Miscellaneous or "special" tunings [edit]

This category includes everything that does non fit into whatever of the other categories, for example (but not express to): tunings designated only for a detail piece; non-western intervals and modes; micro- or macro-tones(half sharps/flats, etc.); and "hybrid tunings" combining features of major alternate tuning categories – most commonly an open tuning with the lowest cord dropped.[74]

Come across also [edit]

- Bass guitar tuning

- Listing of guitar tunings

- Mathematics and music

- Open G tuning

- Stringed instrument tunings

- DADGAD

Notes [edit]

- ^ Sometimes referred to equally warp refraction.

- ^ Musicologist Eric Tamm wrote that despite "considerable effort and search I just could non find a good ready of chords whose sound I liked" for rhythm guitar.[72]

Citation references [edit]

- ^ Denyer (1992, pp. 68–69)

- ^ JustinGuitar. (2020). Acquire the Open up Cord Notes on the Guitar! [Video]. Youtube. https://world wide web.youtube.com/picket?v=CF08-EwA-nY

- ^ Brownish, J. (2020). xi alternate tunings every guitarist should know. Retrieved from https://www.guitarworld.com/lessons/11-alternate-tunings-every-guitarist-should-know

- ^ "Online guitar tuner". TheGuitarLesson.com. Archived from the original on 24 Baronial 2013. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ "Transposing Instruments – Music Theory Academy". eighteen January 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ Creativeguitarstudio. (2015). GUITAR THEORY: Chromatic Chord Progressions [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1DlStHAEg8w

- ^ Brown, J. (2020). 11 alternating tunings every guitarist should know. Retrieved from https://www.guitarworld.com/lessons/11-alternate-tunings-every-guitarist-should-know

- ^ Brennan, Maureen (2008). "Linen lites - drThe drones of swedish folk music". Dingy Linen: xv.

- ^ Weissman (2006, 'Off-the-wall tunings: A brief inventory' (Appendix A), pp. 95–96)

- ^ Caluda, Glenn (v May 2014). "Open Tunings for Folk Guitar". The American Music Teacher. 63 (5): 54. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ Roche (2004, 'Categories of tunings', p. 153)

- ^ Roche (2004, pp. 153–156)

- ^ a b c d Denyer (1992, pp. 158–159)

- ^ Roche (2004, 'Open tunings', pp. 156–159)

- ^ Roche (2004, 'Cross-note tunings', p. 166)

- ^ a b Sethares (2011)

- ^ Roche (2004, 'Modal tunings', pp. 160–165)

- ^ Roche (2004, 'More than radical tunings', p. 166)

- ^ "Notation". Joni Mitchell. Archived from the original on fifteen March 2016. Retrieved twenty March 2016.

- ^ Faherty, Michael; Aaronson, Neil L. (1 October 2010). "Acoustical differences between treble guitar strings of different tension (i.e., estimate)". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 128 (four): 2449. Bibcode:2010ASAJ..128.2449F. doi:10.1121/1.3508761. ISSN 0001-4966.

- ^ Roche (2004, 'String gauges and altered tunings', p. 169–170)

- ^ Powis, Simon (8 April 2018). "Drop D Tuning Tips". Classical Guitar Corner . Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ Bowcott, Nick (ten September 2008). "The Doom Generation: The Art of Playing Heavy". Guitar Earth . Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ Ben Long. "Drib D Tuning". Archived from the original on ten November 2017.

- ^ Teraz Rock (November 2010). "Soundgarden Na 12 Stronach!". Archived from the original on 21 June 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ^ MrHardguitar (13 Apr 2012). "What Is Drib D Tuning Guitar Lesson (how to Tune Guitar to Drop D Tutorial)". YouTube.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Tolinski, Brad (September 1994). "Heavy Mental - Interview". Blue Cricket Media.

- ^ "Guitar Instructor guide". 6 August 2019. Archived from the original on 20 April 2020. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ a b Sethares (2009, p. xvi)

- ^ a b Denyer (1992, p. 158)

- ^ Denyer (1992, p. 160)

- ^ Gold, Jude (December 2005). "Just desserts: Steve Kimock shares the sweet sounds of justly tuned thirds and sevenths". Master course. Guitar Player. [ dead link ]

- ^ a b Annala & Mätlik (2007, p. 30)

- ^ Ophee, Matanya (ed.). 19th Century etudes for the Russian vii-cord guitar in G Op. The Russian Collection. Vol. 9. Editions Orphee. PR.494028230. Archived from the original on iv July 2013.

– Ophee, Matanya (ed.). Selected Concert Works for the Russian 7-Cord Guitar in One thousand open tuning. The Russian Drove. Vol. 10. Editions Orphee. PR.494028240. Archived from the original on 4 July 2013. - ^ a b Timofeyev, Oleg V. (1999). The golden age of the Russian guitar: Repertoire, performance do, and social function of the Russian seven-string guitar music, 1800–1850. Duke University, Department of Music. pp. 1–584. Academy Microfilms (UMI), Ann Arbor, Michigan, number 9928880.

- ^ Grossman (1972, p. 29)

- ^ Sethares (2009, pp. 20–21)

- ^ Sethares (2009, pp. 18–19)

- ^ Baughman, Steve (2004). "Open C". Mel Bay Beginning Open up Tunings. Pacific, Missouri: Mel Bay Publications. pp. eight–14. ISBN978-0-7866-7093-2.

- ^ Guitar Tunings Database (2013). "CCGCEG Guitar Tuner". CCGCEG: Open C via harmonic overtones. Archived from the original on 10 March 2013. Retrieved 20 Feb 2013.

- ^ Persichetti (1961, pp. 23–24)

- ^ a b Sharken, Lisa (15 May 2001). "Mick Ralphs: The rock 'Northward' curlicue fantasy continues". Vintage Guitar. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ^ "List of all Guitar and Piano Transcriptions". GGDGBD. JoniMitchell.com. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ Ellis, Andy (2005). "How to play similar ... Keith Richards". Guitar Histrion . Retrieved 24 March 2013. [ dead link ]

- ^ Blare (1970, p. 164)

- ^ "Piano Chord Chart". 8notes.com. Archived from the original on fourteen June 2017. Retrieved half-dozen May 2018.

- ^ Sethares (2001, p. xvi)

- ^ Cohen, Andy (22 March 2005). "Stefan Grossman- Land Blues Guitar in Open Tunings". Sing Out!. 49 (1): 152.

- ^ http://www.betterguitar.com/instruction/rhythm_guitar/tune_down_half_step/tune_down_half_step.html

- ^ Serna, Desi (2015). Guitar Rhythm and Technique For Dummies. For Dummies. p. fourscore. ISBN978-1119022879 . Retrieved 25 January 2019.

information technology'due south fairly common in rock music for guitarists to tune all of their strings down past a one-half-step

- ^ Denyer (1992, p. 119)

- ^ Sethares (2001, p. 52)

- ^ a b Kirkeby, Ole (ane March 2012). "Major thirds tuning". m3guitar.com. cited past Sethares (2011). Archived from the original on xi Apr 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- ^ White, Mark (Fall 2005). "Reading skills: The guitarist'south nemesis?". Berklee Today. Vol. 17, no. 2. Boston, MA: Berklee College of Music. ISSN 1052-3839.

- ^ Denyer (1992, p. 72)

- ^ Peterson (2002, p. 37)

- ^ Griewank (2010, p. 5)

- ^ Sethares (2001, pp. 54–55)

- ^ Sethares (2001, pp. 58–59)

- ^ Bianco, Bob (1987). Guitar in Fourths. New York Metropolis: Calliope Music. ISBN0-9605912-ii-two. OCLC 16526869.

- ^ Ferguson (1986, p. 76)

- ^ a b Sethares (2001, pp. 56)

- ^ a b c Peterson (2002, pp. 36–37)

- ^ a b Griewank (2010)

- ^ a b c Patt, Ralph (14 April 2008). "The major 3rd tuning". Ralph Patt's jazz web page. ralphpatt.com. cited past Sethares (2011). Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- ^ Griewank (2010, p. ix)

- ^ Griewank (2010, p. two)

- ^ Griewank (2010, p. x)

- ^ Denyer (1992, p. 121)

- ^ Sethares (2001, 'The mandoguitar tuning' 62–63)

- ^ Mulhern, Tom (January 1986). "On the subject area of craft and art: An interview with Robert Fripp". Guitar Player. 20: 88–103. Archived from the original on xvi Feb 2015. Retrieved viii January 2013.

- ^ Tamm (2003)

- ^ Sethares (2001, 'The mandoguitar tuning', pp. 62–63)

- ^ Whitehill, Dave; Alternate Tunings for Guitar; p. 5 ISBN 0793582199

References [edit]

- Allen, Warren (22 September 2011) [30 Dec 1997]. "WA's encyclopedia of guitar tunings". (Recommended by Marcus, Gary (2012). Guitar cipher: The science of learning to be musical. Oneworld. p. 234. ISBN9781851689323. ). Archived from the original on 13 July 2012. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- Annala, Hannu; Mätlik, Heiki (2007). "Composers for other plucked instruments: Rudolf Straube (1717–1785)". Handbook of Guitar and Lute Composers. Translated by Katarina Backman. Mel Bay. ISBN978-0-786-65844-2.

- Bellow, Alexander (1970). The illustrated history of the guitar. Colombo Publications.

- Denyer, Ralph (1992). "Playing the guitar ('How the guitar is tuned', pp. 68–69, and 'Culling tunings', pp. 158–159)". The guitar handbook. Special contributors Isaac Guillory and Alastair M. Crawford (Fully revised and updated ed.). London and Sydney: Pan Books. pp. 65–160. ISBN0-330-32750-10.

- Ferguson, Jim (1986). "Stanley Jordan". In Casabona, Helen; Belew, Adrian (eds.). New directions in mod guitar. Guitar Role player basic library. Hal Leonard Publishing. pp. 68–76. ISBN978-0-88188-423-4.

- Griewank, Andreas (1 January 2010), Tuning guitars and reading music in major thirds, Matheon preprints, vol. 695, Berlin, Germany: DFG research center "MATHEON, Mathematics for key technologies" Berlin, urn:nbn:de:0296-matheon-6755. Postscript file and Pdf file, archived from the original on 8 November 2012

- Grossman, Stefan (1972). The book of guitar tunings. New York: Amsco Publishing Visitor. ISBN0-8256-2806-7. LCCN 74-170019.

- Persichetti, Vincent (1961). Twentieth-century harmony: Creative aspects and practise . New York: Westward. W. Norton. ISBN0-393-09539-8. OCLC 398434.

- Peterson, Jonathon (2002). "Tuning in thirds: A new arroyo to playing leads to a new kind of guitar". American Lutherie: The Quarterly Periodical of the Guild of American Luthiers. Tacoma, WA: The Club of American Luthiers. 72 (Wintertime): 36–43. ISSN 1041-7176. Archived from the original on 21 October 2011. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- Roche, Eric (2004). "5 Thinking outside the box". The acoustic guitar Bible. London: Bobcat Books Limited, SMT. pp. 151–178. ISBN1-84492-063-one.

- Sethares, Neb (2001). "Regular tunings" (PDF). Alternating tuning guide. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin; Section of Electrical Engineering. pp. 52–67. Retrieved xix May 2012.

- Sethares, Beak (2009) [2001]. Alternate tuning guide (PDF). Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin; Department of Electrical Engineering. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- Sethares, William A. (2011). "Alternate tuning guide". Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin; Section of Electric Engineering. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- Tamm, Eric (2003) [1990]. "Chapter X: Guitar Craft". Robert Fripp: From crimson king to crafty primary. Faber and Faber. ISBN0-571-16289-4. Archived from the original on 26 October 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2012 – via Progressive Ears. Zipped Microsoft Word Document

- Weissman, Dick (2006). Guitar tunings: A comprehensive guide. Routledge. ISBN9780415974417. LCCN 0415974410.

Further reading [edit]

- Anonymous (2000). Alternate tunings guitar essentials. Acoustic Guitar Magazine's private lessons. String Letter Publishing. Hal Leonard Publishing Corporation. ISBN978-i-890490-24-9. LCCN 2001547503.

- Hanson, Mark (1995). The consummate volume of alternate tunings. Accent on Music. ISBN978-0-936799-thirteen-one.

- Hanson, Mark (1997). Alternating tunings moving-picture show chords. Accent on Music. ISBN978-0-936799-14-8.

- Heines, Danny (2007). Mastering alternate tunings: A revolutionary organisation of fretboard navigation for fingerstyle guitarists. Hal Leonard. ISBN978-0-634-06569-9.

- Johnson, Chad (2002). Alternate tuning chord dictionary. Hal Leonard. ISBN978-0-634-03857-0. LCCN 2005561612.

- Maloof, Richard (2007). Alternate tunings for guitar. Crimson Lane Music Company. ISBN978-1-57560-578-4. LCCN 2008560110.

- Shark, Mark (2008). The tao of tunings: A map to the world of alternate tunings. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN978-1-4234-3087-two.

External links [edit]

- Allen, Warren (22 September 2011) [30 December 1997]. "WA's Encyclopedia of Guitar Tunings". (Recommended past Marcus, Gary (2012). Guitar nada: The science of learning to be musical. Oneworld. p. 234. ISBN9781851689323. ). Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- Sethares, William A. (12 May 2012). "Alternate tuning guide: Interactive". Uses Wolfram Cdf actor. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

Low E String Is Reading F on Tuner When Checking Intonation

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guitar_tunings

0 Response to "Low E String Is Reading F on Tuner When Checking Intonation"

Post a Comment